Determinism, Chaos and Free Will

Written by Isla Madden

For centuries, the laws of physics were understood through the lens of Newtonian mechanics, in which the state of a system at one moment determines its state at all future times. If one knew the positions and velocities of all particles and the forces acting on them, the future evolution of those particles could, in principle, be calculated. In a deterministic universe, an exact cause produces an exact effect, governed by unchanging laws.

The advent of quantum mechanics in the early 20th century challenged this classical view. At atomic scales, outcomes are described probabilistically rather than with precise predictability. Werner Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle formalizes a fundamental limit to the precision with which certain pairs of properties—such as position and momentum—can be known simultaneously. In many standard interpretations of quantum mechanics, like the Copenhagen Interpretation, this indeterminacy is intrinsic: particles do not have definite values until measured, and outcomes can only be expressed as probabilities. Not all interpretations are indeterministic; hidden-variable theories, such as Bohmian mechanics, preserve determinism but require nonlocal interactions.

Even within classical physics, predictability can fail in practice. Chaos theory shows that nonlinear systems—such as the weather or a double pendulum—exhibit sensitive dependence on initial conditions, meaning infinitesimally small differences in the starting state grow exponentially over time. This “butterfly effect” renders long-term forecasting effectively impossible, even though the underlying laws remain fully deterministic. Chaos undermines predictability, not causality: the same initial state still yields the same outcome, but we can never know all details precisely enough to calculate it far into the future.

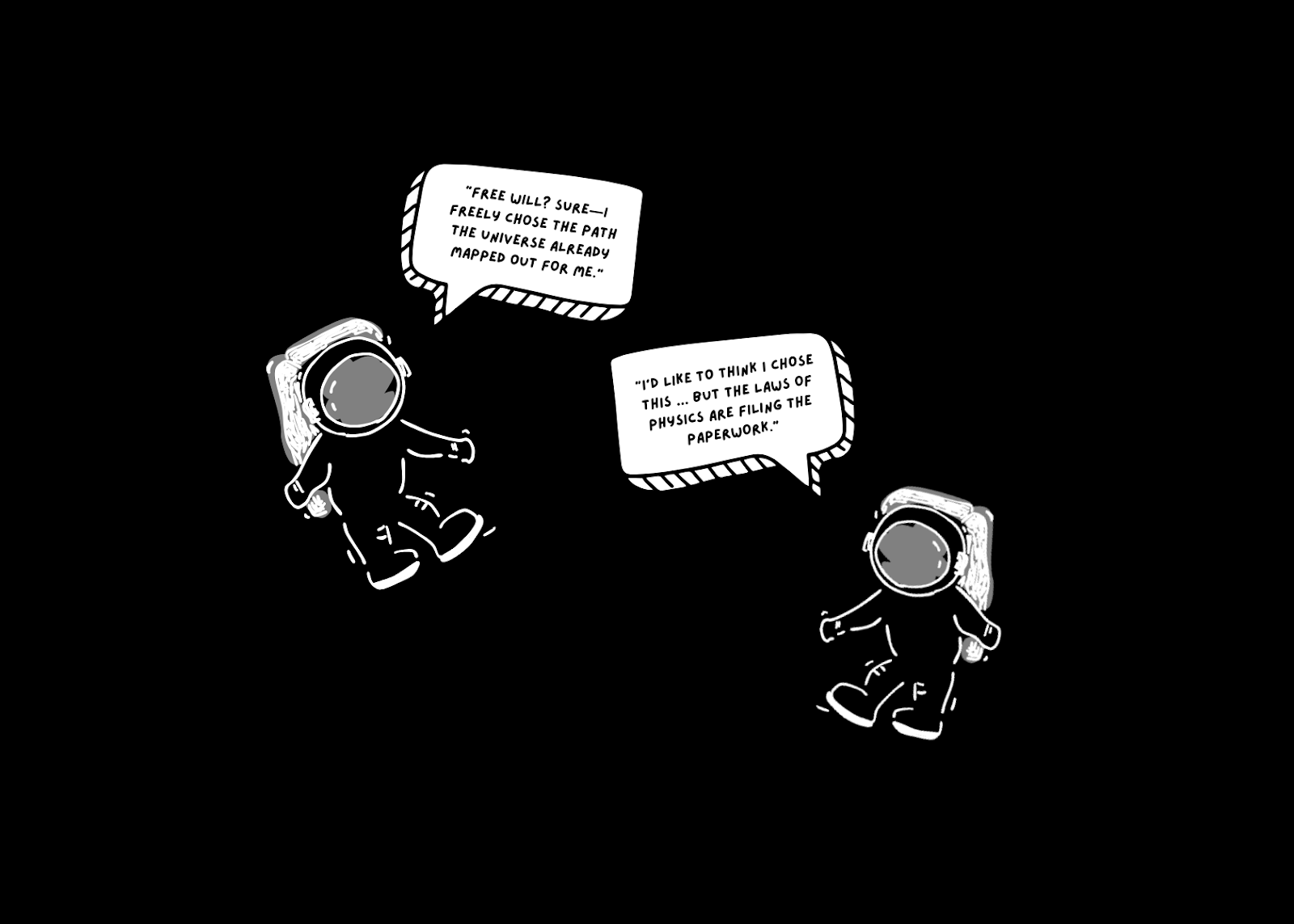

These insights reshape the philosophical debate on free will. Neither strict determinism nor pure randomness by themselves provide a solid foundation for human autonomy. Quantum indeterminacy introduces unpredictability, but randomness alone does not constitute agency. Likewise, a chaotic deterministic system cannot ground genuine choice if every event remains causally anchored in prior states. Contemporary philosophy often distinguishes the lived experience of choice from deep metaphysical claims about causation, suggesting that free will—if it exists—must be understood as an emergent, higher-level phenomenon, rather than as a simple product of physical indeterminacy or determinism.

Modern physics does not decisively prove or disprove free will. Instead, it reframes the question in terms of how complexity, causation, and probability interact in systems like the human brain, rather than whether the universe is absolutely predictable. Beyond merely expanding our knowledge, these insights challenge how we see our world and how we interpret our place within the Universe.